“Other administrations may have lacked the courage–or whatever–to do it.” -Trump on Venezuela referring, presumably, to cojones.

Today I was reading On Microfascisms: Gender, Violence, and Death by Jack Bratich when the first notifications of the U.S. action in Venezuela started coming in. Bratich’s discussion of squadrismo, Italian fascist gangs in the early 20th century who primarily targeted socialist political organizers through intimidation and violence. As an extra-judicial source of violence these kinds of (dis)organized violence is often cited to differentiate Trump from fascism, often by those who argue that the f-word is unnecessarily alarmist and/or inflammatory. The invocation in this instance is not as an historical analogue since, no, organized militia forces have not yet become as regularized as in post-WWI Italy (or Germany). The idea of squadrismo is, however, a useful way to understand the affective draw of a group formed through enacting violence on perceived enemies, taking revenge for harm to their masculine perogative, explicitly flouting the law:

[Italian scholar Nino Valeri] “perceived [squadrismo’s] originality, which

derived not from its love of violence, but from its affirmation of a ‘moral

system pertaining to violence: in other words, violence is elevated to the status of an ethical rule’. (Valli 2000)

Matteo describes a squadristi habitus, a way of life that makes violence a central component of identity–individual and collective–and a defining practice of fascism not merely as a means to obtain power but as an end in itself. The paramilitaries were at times in support of fascist leadership, intimidating or eliminating political rivals, and at other times a useful justification for increasing state power and violence for the purposes of law and order.

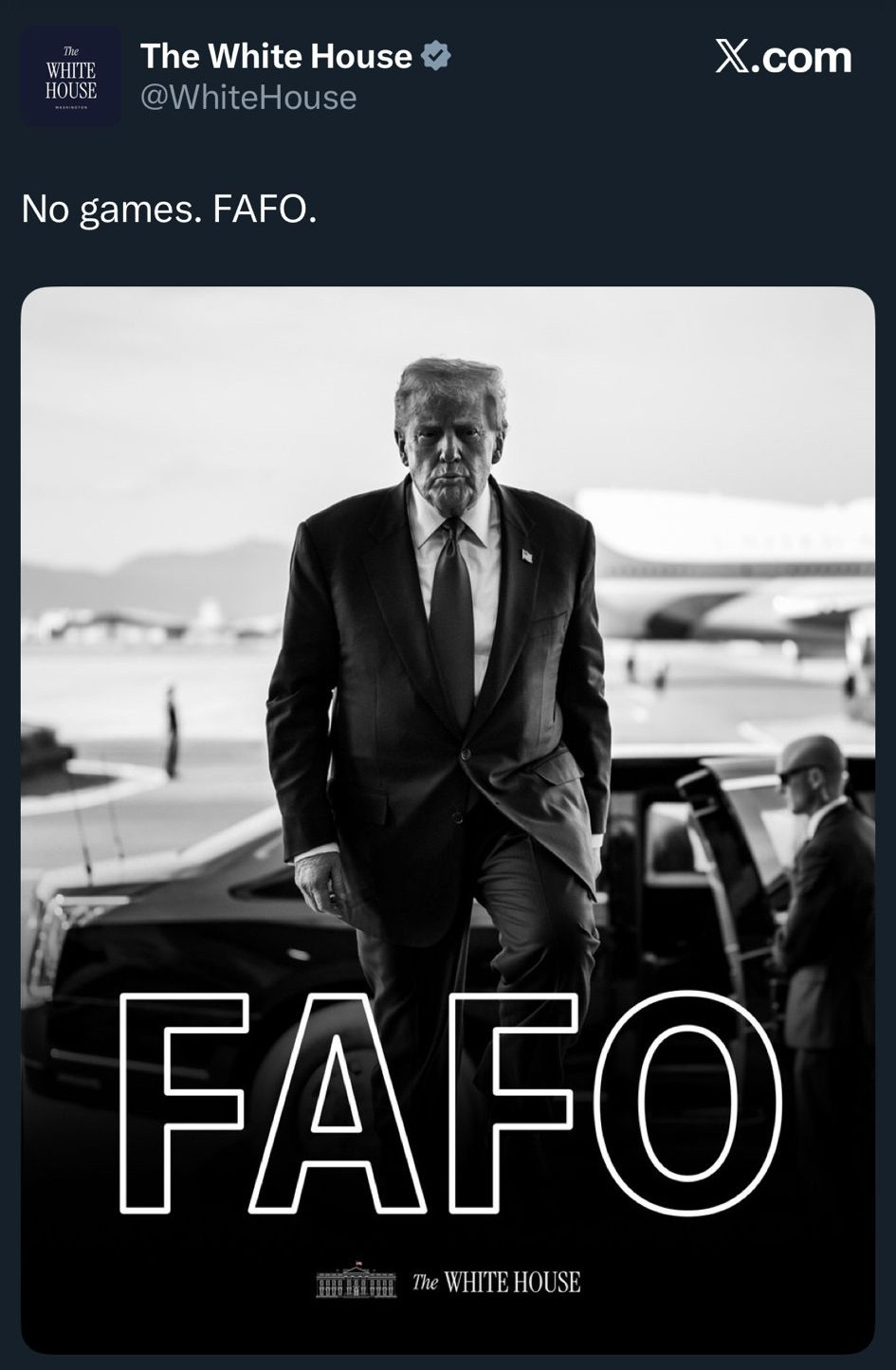

The refrain that “the cruelty is the point” (hat tip to Adam Serwer) has become cliche, too often invoked to wave away sustained attention to the actual violent churn of state policy. Michele Obama’s refrain that “when they go low we go high” reflects the impotence of norms to save us from the real material harms of brute power. Trump has made us all more crass and mean. This is reflected in their regular staging and posting of their violence–Hegseth says Maduro “effed around and found out” (apparently saying fucked is a bridge to far, the actual fucking is not).

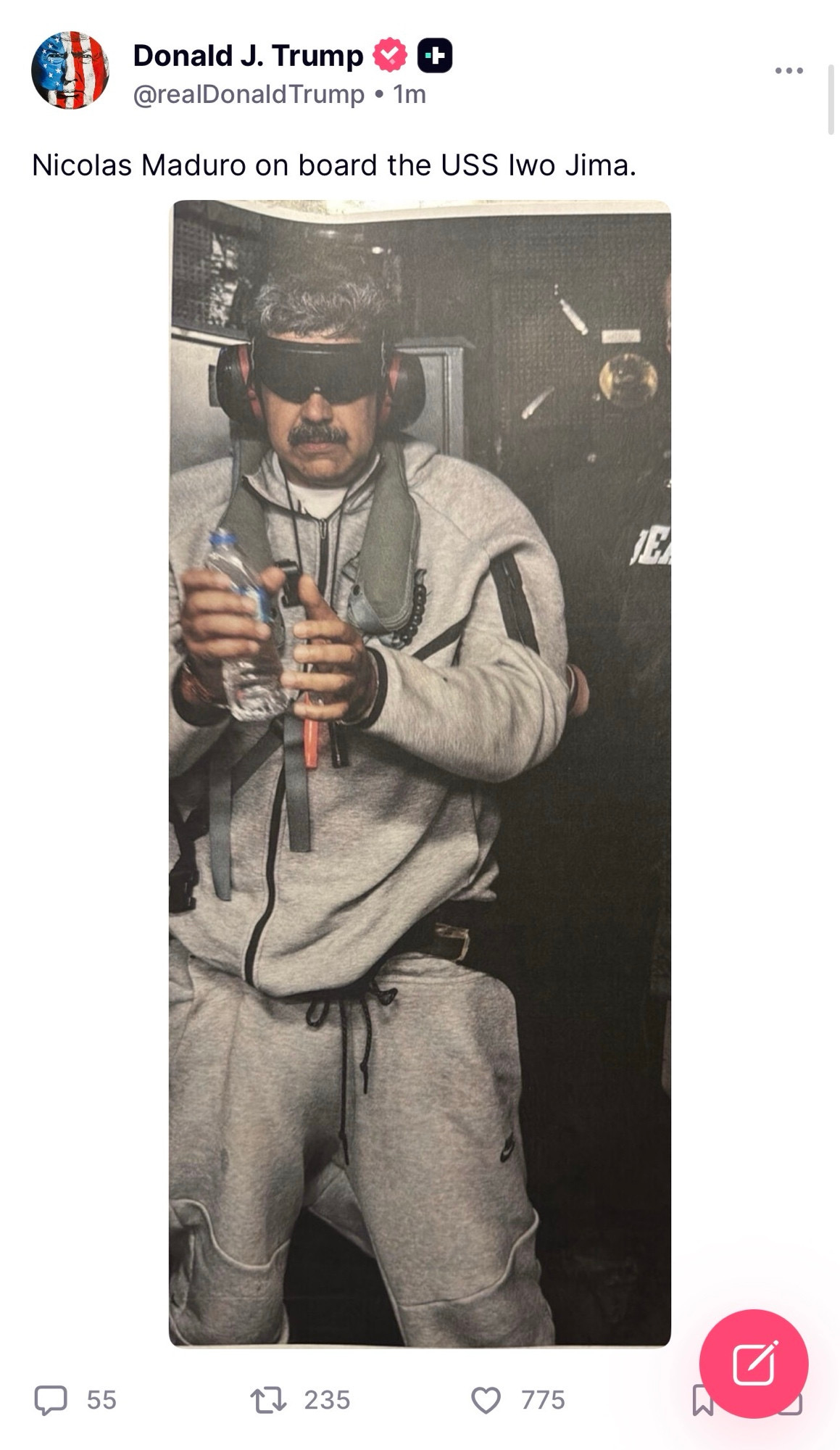

But we are all much meaner, less likely to reign in our baser instincts and we lean in to our desire to see our enemies humiliated and violated as we have been. This is not accidental. The squadrismo staging was explicitly designed to bring this about in their “ritualised forms of destruction and collective physical aggression as well as the persistence of their worldviews, morals and codes of conduct in the regime”. (Saluppo 2020) One historian describes the phenomenology of fascist paramilitary violence as having “deforming effects” on society as a whole, producing a paranoid populace of permanent vigilance and disoriented passivity: “While space contracted, time became uncertain. Everyday life was intensely overshadowed by a sense of uneasiness and trepidation about the immediate future. Fear that something terrible might happen to anyone at any moment disrupted social relations. Whole communities were taken over by forms of paranoia and hyper-vigilance, which generated anxiety and insomnia.” (Saluppo 2020) Like ICE, squadristi often wore masks, concealing their identities to prevent identification and to increase terror in their victims and to disrupt the kinds of interpersonal bonds that might exist in a community and incite empathy. Descriptions of their laughter while humiliating their enemies sound not dissimilar to what Christine Blasey-Ford remembered from her encounter with Brett Kavanaugh, their laughter at her terror in the face of the possibility of sexual violence. Foucault describes fascism’s delegation of violence to a select few, the unimpressive and otherwise inept and impotent, empowered by simply following power.

Male fraternal bonds forged through ritual violence and humiliation were top of mind today when I saw the pictures emerging of “Operation Absolute Resolve”:

Ben-Ghiat, Ruth. 2005. “Unmaking the Fascist Man: Masculinity, Film and the Transition from Dictatorship.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies 10 (3): 336–65. doi:10.1080/13545710500188361.

‘Strongmen’: How a Crisis in Masculinity Paved the Way for Fascism – Byline Times. https://bylinetimes.com/2020/12/28/strongmen-how-a-crisis-in-masculinity-paved-the-way-for-fascism/

MILLAN, MATTEO. “The Institutionalisation of ‘Squadrismo’: Disciplining Paramilitary Violence in the Italian Fascist Dictatorship.” Contemporary European History 22, no. 4 (2013): 551–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43299403.

Saluppo, Alessandro. “Paramilitary Violence and Fascism: Imaginaries and Practices of Squadrismo, 1919–1925.” Contemporary European History 29, no. 3 (2020): 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960777319000390.

Toscano, Alberto. “Mapping Microfascism.” In The Routledge Handbook on the Lived Experience of Ideology, pp. 329-345. Routledge, 2025.

Leave a comment